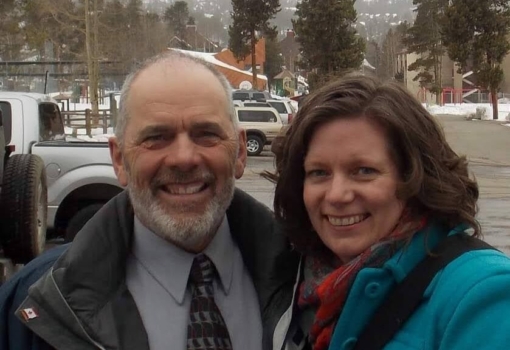

Jan Pezzaro

“But there is something on the chest x-ray. A cloudy spot on your lung. It’s probably nothing to be concerned about, but if it will make you feel better, I can refer you to a lung specialist,” said my GP.

I watched as my husband expertly sabred a bottle of expensive champagne, sending the muselet deep into the garden of our gracious West Vancouver home. With a sigh of gratitude, I took in the beauty of the night and the excitement-flushed faces of my daughters as we rang in the New Year. Welcome, 2015! I anticipated the golden years ahead with ample time to welcome a generation of grandchildren and greet countless sunrises in exotic destinations with my beloved family. Within months, I was deep inside an emotion-riddled labyrinth menaced by the specter of lung cancer—come to steal my breath and end my life—and burdened with guilt at my role in summoning this monster.

New Year’s Eve 2016 found me weeks away from surgery for the removal of my right upper lung, which harbored a cancerous tumor. Fueled by a lifetime of exposure to the horrors of cancer as depicted in films, books, and the media, I was convinced I had been handed a death sentence. However, the pathologist’s post-surgical report confirmed the margins surrounding the tumor were clear of cancer cells. I had been granted a reprieve.

I realized I was in a race between death by disease or death by cure, but I had gained a new appreciation for the mind game of surviving cancer. Determined to complete my degree and aided by recent advances in surgical techniques, I plunged into my studies and redirected my focus from the fear of dying to the joyfulness of living. “

Two years passed almost without incident. Periodic CT scans did not detect the recurrence or emergence of cancer—gradually increasing my confidence that the malignancy was a one-time unfortunate event. That optimism was shattered in 2019 when the radiologist identified a new tumor in the remaining tissue of my right lung. Almost simultaneously, the world plunged into the pandemic. COVID patients overran hospitals, and the wait times for CT scans increased by an order of magnitude. Overwhelmed by a sense of mounting vulnerability and filled with dread at the idea of facing cancer and another lung surgery, I doom-scrolled from the safety of the master bedroom.

In an unexpected twist, my doctors offered surgery or an alternative—a new form of ultra-high radiation called SABR. Weighing the long recovery time and lung tissue loss associated with surgery against the less invasive impacts of SABR, I chose the new treatment. This decision turned on me shortly after completing 60 Grays of radiation when I realized there would be no post-SABR pathology report, as there wasn't any tissue to test and, therefore, no proof the treatment had eradicated the cancer. Swamped with shame at the years of smoking that set in motion the murderous mutations now menacing me and deluged with despair at the thought the cancer might continue to grow and spread, depression ambushed me.

With my resilience in tatters, I began a frantic search for a new sense of purpose. It arrived in the unlikely form of the opportunity to return to university at age sixty-six. I was set to begin my master's program in the summer of 2022 when doctors found a third cancer in my previously unaffected left lung. I realized I was in a race between death by disease or death by cure, but I had gained a new appreciation for the mind game of surviving cancer. I chose the certainty of surgery. Determined to complete my degree and aided by recent advances in surgical techniques, my recovery was swift. I plunged into my studies and redirected my focus from the fear of dying to the joyfulness of living.

Seven years after cancer made its first appearance and threatened to rob me of all I held most precious, the golden years arrived. I traveled to Los Cabos, Mexico, with my extended family and received final absolution from my daughters for smoking too much and working too much. Their love was unconditional and unwavering. I put down the burden of guilt for good.

The experience taught me that cancer is a terrifying diagnosis and a formidable opponent, but early-stage lung cancer need not be a death sentence. I resolved to become an advocate for early detection and to push back against the stigma of lung cancer as a “smoker’s disease.” I will not let the tobacco industry and their advertising Mad Men win; no one deserves lung cancer, and no one deserves to die from it.

Read more about Jan’s journey and the importance of early detection as featured in Newsweek.